Nan Goldin: This Will Not End Well

The Goldin Variations

An architectural recital by Hala Wardé

I never wanted to be a photographer. I always wanted to be a filmmaker. I found a way to make films out of still images. Making slide shows gives me the luxury of constantly reediting to reflect my changing view of the world.

Nan Goldin

This Will Not End Well

How did it begin?

How to describe the genesis of this project?

How to speak of the exhibition as a visible experience of thought?

Of the meeting of Art and Architecture?

Of the development of ideas and forms in the mind of an architect?

It begins with a selection made by Nan Goldin, at the invitation of Stockholm’s Moderna Museet, of artworks, slideshows, and films, brought together for the first time in one place for a retrospective.

The works are unique and different, even though they were born of the same inspiration and we can draw parallels. Some films, more well-known than others, have moved and shaken up generations with their powerful content. These works are ageless, for regardless of how recent or old they are in her output, Goldin has never ceased reworking them, perfecting them, keeping them alive.

To design this exhibition, Goldin calls her architect. It’s not the first time that we’ve worked together, for we collaborated on her Versailles exhibition Visible/Invisible—a truly wonderful experience. The architect starts by listening attentively to the artist explaining her project, then asks herself:

How to orchestrate the spatial presentation of these very different pieces?

How to preserve their individuality while enabling a conversation between them?

How to find the unity needed for visual and spatial coherence?

How to handle the proximity of the works to each other?

What shape? What material? What lighting?

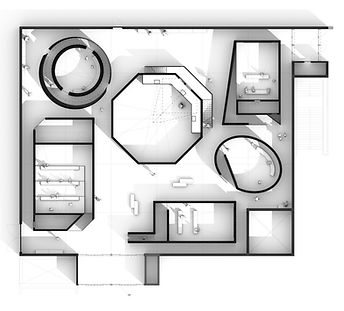

The first idea is to organize the whole in the manner of an urban plan, a village of slideshows, and to create specific architectural designs for each of Goldin’s works. Visible structures that express themselves like living bodies, carefully positioned on the stage to create a moment of harmony, like instruments of a band playing the same score.

In order to be as close as possible to the “subject” for the sake of imagining the form that each of these works will take, the architect spends time getting to know them better, viewing the films again and again, listening to Goldin talk about them, or watching her keep silent, convinced that the formal response is found in the works themselves.

The shape of these structures is born, one by one, each specific and inspired by its subject, even if their dimensions are initially dictated by the technical constraints of projections, which require very specific configurations. Some are reminiscent of existing places that these works once inhabited, such as the Salpêtrière Chapel in Paris for Sister Saints, and Sibyls, a movie theater for The Ballad of Sexual Dependency, or the gilded atmosphere of a nightclub for The Other Side. Others evince a variety of sensations connected with the films, such as the labyrinthine effect of a circular shape for Fire Leap, a slideshow about children, or the claustrophobic feel of a dropped ceiling for Memory Lost, about the darkness of addiction.

At Stockholm’s Moderna Museet, six architectural structures thus appear in an ambient penumbra, dark bodies composing a landscape of multiple geometries. Curved, straight, or angular, these shapes stand in their uniqueness, converse, rub against, and nearly touch one another, then pull apart, frozen in an instant of choreography. Their layout is perfectly measured, anchored in the existing architecture of the place.

Thick fabrics espouse the architecture of these forms, closely enveloping their structure, to protect the interior lighting and music and their beating heart. A first interior skin is doubled by a second exterior skin that folds back over, then cracks open slightly to discreetly invite the visitor in.

The entrance to these rooms is not always obvious and visitors sometimes have to walk along or around the structure to find the opening, like the secret crack to a dark body one awakens. In the twilight atmosphere of the place, a light, a color, or a slight escaping sound draws the visitor to it.

To discover the work inside, visitors have to penetrate into the darkness of each of these bodies, and then walk through a passageway that prepares them for their entry into the film itself. These in-between spaces are essential. They function as sound locks or light locks, but also as paths of initiation into the work, which assume a variety of forms: the dark and narrow low-ceiling corridor or, on the contrary, the high-ceiling space, punctuated by a vertical light shaft; vertiginously oblique and circular walls or steep stairs winding along a facade. These passages trigger or foreshadow the first sensations, the beginning of an emotion, before the ultimate one that Nan Goldin’s work will provoke.

This exhibition, which is taking its first steps in Stockholm, is destined to travel. It is already scheduled to be shown at other prestigious venues: the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam, in Ludwig Mies van der Rohe’s masterpiece, the Neue Nationalgalerie in Berlin, Pirelli HangarBicocca in Milan, and Grand Palais in Paris. The installation will be renewed with each new space, and the body of works may expand. The forms remain constant, but the staging variable. The structures take their stage clothing with them when they move and are repositioned in a new spatial order, constantly in conversation with each other and with the architecture.

A perpetual voyage in the universe of Nan Goldin: This will not end well.

Hala Wardé